The Haas Effect, also known as the precedence effect, has long been a cornerstone in the world of audio engineering, particularly in the realm of multitrack mixing. This psychoacoustic phenomenon, first identified by Helmut Haas in 1949, describes how humans perceive the direction of sound when two identical sounds arrive at the ears with a slight delay. In modern music production, understanding and applying the Haas Effect through pre-delay techniques can dramatically enhance the spatial depth and clarity of a mix.

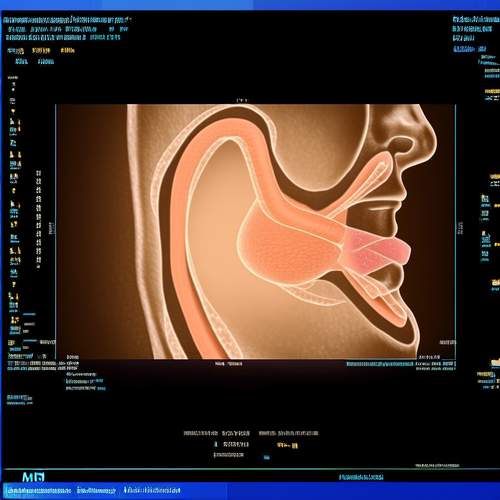

At its core, the Haas Effect explains why we localize sound based on the first arrival rather than subsequent reflections. When two identical sounds reach the listener within about 1-35 milliseconds of each other, the brain perceives them as a single sound coming from the direction of the first arrival. This principle becomes incredibly useful in mixing, where engineers can manipulate the perceived width and placement of instruments without altering their tonal characteristics. By carefully applying pre-delay to certain elements, mixers can create a sense of space that feels both expansive and natural.

In practical application, pre-delay settings between 5-30 milliseconds often yield the most musical results for creating stereo width. For instance, when working with a mono guitar track, sending a duplicate to the opposite channel with 15ms of delay can produce a convincing stereo image without phasing issues. The key lies in finding the sweet spot where the delayed signal remains fused with the original while providing sufficient separation for the ear to perceive width. This technique proves particularly effective on rhythm guitars, keyboards, and backing vocals that need to occupy space without dominating the mix.

Modern digital audio workstations have made implementing Haas Effect techniques more accessible than ever. However, the convenience of plugins shouldn't overshadow the need for critical listening. The interaction between pre-delay times and the musical content significantly impacts the final result. Faster tempos generally require shorter delay times to maintain musical cohesion, while slower ballads might accommodate slightly longer intervals. Additionally, the frequency content of the source material plays a role—denser, harmonically rich sounds often mask timing differences better than sparse, transient-heavy material.

One creative application involves using varying pre-delay times across different frequency bands. By applying shorter delays to high frequencies and progressively longer delays to lower frequencies, engineers can simulate the natural way sound waves behave in physical spaces. This multiband approach can prevent the sometimes unnatural "smearing" that occurs when the same pre-delay time applies across the entire frequency spectrum. Such techniques require careful automation and EQ work but can yield incredibly three-dimensional results when executed properly.

The relationship between Haas Effect pre-delay and early reflections warrants special consideration in mix decisions. While pre-delay creates the initial spatial cue, the subsequent early reflections (typically occurring between 30-80ms after the direct sound) contribute significantly to our perception of the environment. Many engineers find that aligning pre-delay times with the song's rhythmic structure—often syncing to note values like 16th or 32nd notes—creates a more musically integrated spatial effect. This approach ensures the artificial spatial cues feel like an intentional part of the production rather than an afterthought.

Potential phase issues remain the primary concern when employing Haas Effect techniques. When the same signal appears in both channels with minimal time difference, certain frequencies may cancel out when the mix collapses to mono. This proves particularly problematic for radio play or club systems where mono compatibility is essential. Savvy engineers often check their Haas-processed tracks in mono throughout the mixing process, making subtle adjustments to delay times or employing complementary EQ curves to minimize phase cancellation. Some even use mid-side processing to ensure critical elements remain present in the center image while the widened elements provide stereo interest.

The psychological impact of the Haas Effect in music production shouldn't be underestimated. When used tastefully, these spatial cues can create an immersive listening experience that draws the audience into the musical performance. The slight timing differences between channels can add a sense of movement and life to static recordings, particularly important in today's productions where many elements originate from perfectly quantized digital sources. This psychoacoustic trickery taps into how humans naturally process sound in real environments, explaining why well-executed Haas techniques often sound more "real" than artificial stereo wideners or chorus effects.

As with all mixing techniques, the Haas Effect pre-delay works best when serving the song rather than becoming an obvious effect. The most successful applications go unnoticed, simply making the mix feel wider and more engaging without calling attention to the processing itself. In an era where listeners consume music through everything from high-end stereo systems to mono smart speakers, understanding these psychoacoustic principles becomes increasingly valuable. The Haas Effect remains one of those rare scientific discoveries that translates perfectly into artistic application, allowing engineers to manipulate space and dimension with nothing more than milliseconds of timing difference.

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025

By /May 30, 2025