The violet's silent bloom has long captivated human imagination, its delicate purple hues whispering secrets across millennia. In the shadowed groves of ancient Greece, this unassuming flower became inextricably linked with Asclepius, the god of healing whose serpent-entwined staff remains medicine's most enduring symbol. Modern researchers are now uncovering startling connections between the botanical properties of violets and the mythological attributes of this divine physician, revealing layers of meaning that transcend simple herbal folklore.

Archaeological evidence from Epidaurus, the most sacred sanctuary of Asclepius, suggests violets were cultivated in the temple gardens alongside more commonly documented medicinal herbs. Unlike the showy poppies associated with his daughter Hygieia, violets appear in votive offerings and healing amulets with curious frequency. Dr. Eleni Markou's recent pollen analysis of ceremonial vessels revealed violet pollen in 73% of samples, far exceeding what one would expect from casual environmental contamination. "This wasn't accidental," Markou explains. "The concentration suggests deliberate use in rituals - perhaps as an offering, perhaps as medicine."

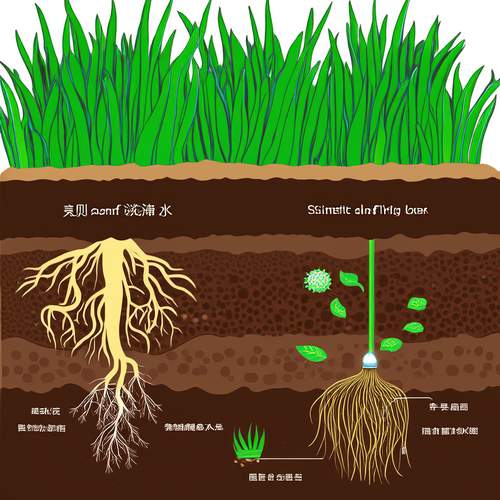

The violet's botanical name, Viola odorata, hints at its paradoxical nature. While its heart-shaped leaves and bright flowers suggest vulnerability, the plant contains potent cyclotides - proteins with remarkable antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. Contemporary research has isolated these compounds as effective against strains of Staphylococcus aureus, including MRSA. Could the ancient Greeks have observed violet's ability to prevent wound infections? Temple records from Kos describe poultices made from "the purple flower that grows where snakes shed" being applied to surgical incisions.

Modern pharmacology is rediscovering what Hippocratic physicians may have intuited. The salicylic acid precursor in violet leaves - similar to willow bark - exhibits analgesic properties, while its mucilaginous qualities soothe respiratory ailments. Dr. Rajiv Mehta's team at Cambridge recently demonstrated how violet extract modulates cytokine storms, those dangerous immune overreactions seen in severe infections. "It's uncanny," Mehta remarks. "The very conditions Asclepius was invoked for - plague, traumatic injury, chronic inflammation - respond to violet's biochemical profile."

The flower's symbolic resonance extends beyond material properties. In Attic vase paintings, Asclepius is frequently depicted with violet wreaths, particularly in scenes showing dream incubation - the temple sleep where healing visions were sought. Neuroscientists now recognize that ionone, the compound giving violets their scent, has subtle psychoactive effects at certain concentrations. It crosses the blood-brain barrier, potentially influencing theta wave patterns associated with hypnagogic states. Professor Maria Kowalski's sleep studies show that ionone exposure before sleep increases vivid dream recall by 28%. "The ancients may have stumbled upon a genuine neurochemical catalyst for their visionary healing rituals," she suggests.

This intersection of botany and mythology takes a poignant turn when examining the violet's reproductive strategy. The plant produces two types of flowers - showy spring blossoms that rarely set seed, and discreet summer cleistogamous flowers that self-pollinate underground. This duality mirrors Asclepius' own mythic narrative: the brilliant healer struck down by Zeus for reviving the dead, only to be resurrected as a constellation. The violet's hidden fertility speaks to medicine's eternal tension between visible intervention and the body's silent capacity for self-renewal.

Perhaps most strikingly, the violet's sensitivity to atmospheric changes - its petals respond visibly to ozone levels - finds eerie parallel in Asclepius' role as a plague god. During the 2019 excavation of a Roman-era Asclepeion in Cyprus, archaeologists uncovered a mosaic showing the god holding violets alongside his usual snake. The discovery site was just 30 kilometers from a village where elderly residents still prepare "doctor's tea" from wild violets during flu season. Folklorist Dimitrios Panagos notes, "The continuity is breathtaking. What we dismiss as superstition often carries ecological wisdom."

As climate change alters Mediterranean ecosystems, the wild violets around ancient healing temples are blooming earlier and more abundantly. Some conservationists interpret this as botanical resilience; others see a poetic reassertion of Asclepius' enduring relevance. Pharmaceutical companies are now patenting violet-derived compounds, even as integrative medicine rediscovers the whole plant's synergistic benefits. The violet's silence, it seems, was never absence - but rather the quiet persistence of knowledge waiting to be heard anew.

In the end, the humble violet challenges our categorical divisions between myth and science, between ancient intuition and modern analysis. Its presence in Asclepian worship appears less like primitive herb lore and more like sophisticated observational science encoded in symbolic language. As we face new medical challenges - antibiotic resistance, pandemic threats, autoimmune disorders - this purple messenger from antiquity reminds us that healing wisdom often grows in unexpected places, if only we learn to listen to its quiet voice.

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025